|

From the Archives:

"Coffee Shop: An Interview with Rick McCammon"

by William G. Raley

|

Editor's note:

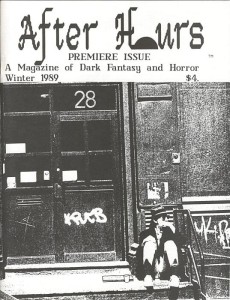

This article originally appeared in the fanzine After Hours,

Winter 1989. After Hours was published by William G. Raley,

who conducted this interview. It is reprinted here

with the permission of William G. Raley.

Thank you, William!

ROBERT R. McCAMMON and I have a few things in common: we're both from the

Heart of Dixie; we're both Cancers; and we both have an affinity for

fiction that comes out after dark. He is the author of several novels,

including They Thirst, Mystery Walk, and Usher's

Passing. Swan Song tied

with Stephen King's Misery for the inaugural Bram Stoker novel award for

superior achievement, conferred by the Horror Writers of America (HWA). His

latest novel is Stinger, from Pocket Books.

After Hours: Did you grow up in Birmingham?

Rick McCammon: Yes, I did.

AH: Where did you go to school?

RM: I went to the University of Alabama.

AH: Your first novel, Baal, was published when you were 26. Did you start

writing full-time then?

RM: I began writing full-time when I finished Bethany's Sin,

which was actually the third book I wrote but was published second after

Baal, with The Night Boat being published third.

As a kid, I'd written short stories, poems and stuff, but I never imagined

I'd ever be able to make a profession out of writing.

AH: Birmingham's a large city—do you spend time in rural Alabama when

writing a story, or draw from experience?

RM: Birmingham's a great place because there's city here and then there's

rolling farmland and forest not too far away. I live in a semi-rural area,

I guess you might say, with forest, in my backyard. My area is very

quiet, though a huge shopping center isn't far. Just ask Joe Lansdale; he

knows all about it. Anyway, Birmingham's a good mix of city and country.

AH: How has being from the South affected your work? How prevalent do

you feel regionality is within the rest of the horror genre?

RM: I began writing by consciously not including Southern characters and

locales in my work. I didn't want to be a "Southern writer," so much as I

wanted to be a writer who lives in the South. But I'm finding I am writing

more and more about the South, simply because it's in me. Charles Grant

said something interesting about Swan Song. He said he thought all the

characters in it were Southern, whether they were described as being from

the South or not. I think that's probably true, simply because all the

characters in a book—good or bad—are extensions of their creator. I

don't consciously hear myself speaking in a Southern accent, but I guess

that's my voice.

AH: What does the South offer in the way of settings and atmosphere that

other regions cannot provide?

RM: That's difficult to answer, because I haven't lived in other regions.

I think all regions of the country have their power and charm, but when I

think of the South I always think of green. Green fields, green forest;

a primeval bursting forth of life. Emotions are high and raw in the South,

there's probably more violence here than in other parts of the country.

But it's a beautiful place, with much forest that comes right up to your

backdoor. I think the South has an untamed spirit—a private, secretive

spirit—and I like that very much.

AH: Can you offer any explanation why you're the only major horror author

from Alabama?

RM: I've killed all the other ones,

AH: What advice do you have for writers in small-town America who want to

add local flavor to their work?

RM: Go out and eat a locale.

I'm serious about that. Mental consumption. It's important to absorb as

much of any locale as you can, including local people. That means attention

to details: accents, what people wear, the kind of cars they drive,

whatever. Writing is a process of gathering information, refining it, and

making a story out of it. I think learning the history and folklore of

your area is also very important.

AH: Do you have any advice for successfully published authors of dark

fantasy and horror short stories having difficulty selling novels? Do you

think most writers try novel-writing too soon?

RM: My advice is to stick with it. Get feedback from people you trust.

Keep working. Work everyday. Don't believe that anything having to do

with writing is easy, but do believe that everything having to do with

writing is worth the effort.

AH: Do you have any opinion why so few good horror novels and stories are

made into films?

RM: I think many good horror novels and stories are made into films,

Unfortunately, they aren't good films. Writing a novel or a story is a

solitary craft, where the writer is in total control of his or her efforts.

Writing a screenplay, on the contrary, may be done by a roomful of people

who have been assigned to do the job. So it's no longer a labor of

love—or even an item of particular interest—but instead a means to earn

a paycheck at the end of the week. There's also the LCD factor—the

"lowest common denominator" factor—at work in Hollywood. I don't think

most screenwriters and unfortunately very few directors seem to feel the

motion picture audience has much intelligence. So: crap in, crap out.

AH: Are there plans to turn any of your novels into movies?

RM: A few of my works are optioned. Whether anything becomes a movie or not

is anyone's guess. Actually, a movie based on one of my books could be a

horrible disaster; in fact, the odds are greater that it would be a

disaster rather than being successful or true to the book. So, my feeling

is: nice if it happens—maybe—but if it doesn't happen, so what?

AH: Are you like other well-known horror authors in that you have a highly

developed sense of humor? Why do humor and horror coexist so well?

RM: Sure, I have a highly developed sense of humor! For instance, do you

know why the moron threw his clock out the window? Because he wanted to see

time fall!

See? Isn't that funny? I've got a million of 'em!

I think horror and humor are flip sides of the same coin. It's more of a

shock to flip back and forth between them, and I think humor strengthens

horror while at the same time making a book more plausible. I mean, nothing

is ever all horrifying, just as nothing is ever all humorous.

AH: What do you think is the scariest location in Alabama for a story to

take place?

RM: Two locations: my file-cabinet and closet. Both are terrifying.

AH: You're on the board of trustees of the HWA. What benefits do you feel

organizations such as this offer to writers?

RM: A sense of belonging, of being part of a larger fabric. I think

writers—people who basically work in a mental, solitary coalmine—need

that sense of belonging to a group of like-minded souls. I know I certainly

do, and over and above the professional implications of what HWA can do for

writers in the marketplace, HWA is a great gathering point for writers in

the genre.

AH: Do you use a PC to type your manuscripts?

RM: I work on a Xerox 645S Memorywriter, which is a combination typewriter

and computer. I just love to pop those ribbon cartridges in and out and

not get my fingers all black like I used to. Also, I don't have to use

that white correction gunk anymore. A real pro, huh?

AH: What's the best source of reading material for new writers wanting to

avoid overdone plots?

RM: Don't focus on reading primarily horror fiction. Read histories,

biographies, books on art, music, astronomy, or fiction in other genres. In

other words, broaden your reading interests beyond horror fiction and let

your mind roam in new territories.

AH: Do you plan to continue writing short stories in addition to novels?

RM: I hope so. I enjoy doing short stories as a break from longer works.

AH: How many rewrites do your short stories typically go through?

RM: Three or four.

AH: Your current novel, Stinger, is about a duel of wits and force between

two alien creatures, set in West Texas. How did the idea for the plot come

about?

RM: I had always wanted to do an elemental, action work. I loved The

Magnificent Seven as a kid, and wanted to do kind of a punk version of

it. I'd had it in mind for a long time, and needed to find a time when I

could fit it into my schedule.

AH: Did you go to Presidio County, Texas, for the background for Stinger?

RM: No, I didn't. I did a lot of research on the area. I wanted it to be

kind of an outer space western. I'd seen the movie Rio Bravo set

in that county, and realized that was the type of setting I wanted.

AH: On what projects are you currently working?

RM: I've recently finished a novel called The Wolf's Hour, set

during World War II. It'll be out in March. I have a book of short stories

and novellas coming out in October called Blue World, and I'm

working on a new book set in Hollywood.

AH: Do you think the South is being portrayed fairly within the horror

genre?

RM: I think people seem to be afraid of the South, particularly if they've

never visited the South before. It's amazing how many people think we

either raise pit bulls down here and chew the heads off chickens or we sit

on Tobacco Road and scratch our chigger bites. Ain't so, y'all.

AH: Describe your work environment. Are you still writing between 10 p.m.

and 4 a.m.?

RM: Yes, I do write on the graveyard shift. It's a lot quieter, no phones

to deal with. I have an office with a view of the sky and the forest. I

listen to music as I work, and I try to do five to seven pages a day.

Finished pages, that is, which is why working on a Memorywriter with a

display screen really cuts the time. I can do all my editing an the

screen, press a button, and out emerges—if all goes well—a finished

page. I work every night and also try to get in some work during the day

too. I think it's important to have regular working hours, and a place

where your typewriter is permanently set up so you know when you sit down

at that place that you're there to work.

AH: Do you have any pets?

RM: No, but my cousin Rex lives in the attic. He has been known to get

loose sometimes. Often he makes his way to my typewriter and mangles

works in progress. He has an affinity for power tools, and he likes

midget wrestling. Chet Williamson knows all about him, poor Chet.

|