|

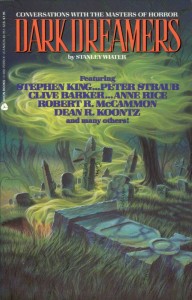

From the Archives:

"Robert R. McCammon"

By Stanley Wiater

From Dark Dreamers: Conversations with the Masters of Horror

published by Avon Books in 1990

|

Unlike Stephen King (four book attempts before Carrie) or John

Saul (ten novel attempts before Suffer the Children), Robert R.

McCammon apparently did it right his first time out. For even though he

intended to make his career in writing as a journalist, no one was more

surprised than he when that first attempt at a novel, Baal, was

published in 1978. McCammon was all of twenty-six. Since that time he has

published nine more novels and a growing body of acclaimed short

stories, recently collected in Blue World. The novels include

Bethany's Sin, The Night Boat, They Thirst,

Mystery Walk, Usher's Passing, Swan Song,

Stinger, The Wolf's Hour, and this year's Mine.

Although his popular novels are yet to be filmed by Hollywood, two of

his short stories ("Makeup" and "Nightcrawlers")

were adapted for the television series "Darkroom" and

"The Twilight Zone," respectively. In its original form, or

as it was adapted for television, "Nightcrawlers" is one of

the most terrifying examinations of the power of the human mind to bring

into reality its own worst nightmares.

Regardless of the usual cliches that go along with being labeled a

creator of tales of fear, in person the soft-spoken Rick McCammon more

accurately represents the finer qualities embodied by the phrase a

Southern gentleman. (Admittedly yet another stereotype, but

certainly an admirable one.) His consideration of other writers in the

field extends back to 1984 when he originated the idea for the Horror

Writers of America, a professional guild which currently has some 400

members. One of the reasons McCammon started the organization was the

belief that horror writers needed to "have a place they could call

home," in the manner of the Science Fiction Writers of America and

the Mystery Writers of America. Like the organization he founded,

McCammon's career has been growing at a rapid rate, with the end nowhere

in sight.

He still lives in his native city of Birmingham, Alabama, with his wife

Sally, and his work has often been critically recognized as possessing a

depth and a maturity which belies the author's age. Booklist has

described him as, "A true master of the gothic novel."

Perhaps one of the ultimate signs of this writer's popularity is

evidenced by the newsletter (Lights Out!) devoted to the man and

his writings. Even though he feels he is just beginning to reach his

stride as an author, book-length critical examinations of his work are

already in-progress.

Wiater: When you went to college, it was to major in journalism.

You had no intention at that point of becoming a novelist?

McCammon: When I finished school, it was when All the

President's Men came out, and everybody wanted to be a

reporter, so I couldn't find a job as one. I found a job in the

advertising department of a local department store. It was a terrible

job and wasn't what I really wanted to do. So I realized the only thing

I could do was to try to write a novel. I'd entertained the idea of

writing one, but never thought I'd be successful at it. Because who

really thinks they can be successful with a first novel? And whoever

thinks they can write something someone will buy and like? So I

was just astounded when my first novel was bought. And I'm still

astounded, because I really don't think Baal is a very good book,

though it was the best I could do at the time. It mirrored a lot of

what I was feeling, because at the time I was very angry, very

frustrated and upset about a lot of things.

Wiater: Was it a conscious decision to write a horror novel, or

was that simply a subject you thought had a chance of selling?

McCammon: Yes, it was something that had always been my interest,

and I think it's the most difficult question to answer: Why do you write

horror? I don't know what went into me to make me write horror. But I

had the same interests as you—I read Famous Monsters of

Filmland when I was a kid, and loved collecting all those. I went

to monster movies. But monster movies scared me [laughs]!

They scared me to death when I was a kid—I just couldn't watch 'em!

So maybe now, by writing horror novels, I'm forcing myself to watch—to

sit and look at—things I was fearful of as a kid.

Wiater: Tell me some of your early influences.

McCammon: With the exception of Ray Bradbury, I can't honestly

say I was influenced by anybody as much as I just liked to read.

People may say, "I was influenced by this writer and I was

influenced by that writer," but I believe horror writers are really

influenced most of all by their childhoods. I wonder if most horror

writers had happy childhoods. I wonder if things have happened that

made us this way—it seems like we're always trying to get back to our

childhood. Trying to find something we lost, or correct something we

missed. Or purge it. Perhaps you can purge something in a book, and it

seems to come back to you. I don't know what that is; perhaps that's just

our bent as horror writers.

Wiater: Unlike some authors who have reached a noticeable degree

of success in this field, you don't seem to be embarrassed to be

primarily recognized as "Robert McCammon, horror writer." I

ask this because I've had others tell me that what they really write are

"novels of fear" or "dark fantasy." Anything so as

not to be considered a writer of horror.

McCammon: Well, I'm not embarrassed. In fact, I'm very

pleased to be associated with the field. I'm very pleased with what

horror can be for its millions of fans. I think those labels like dark

fantasy are glossing over what horror really is. I think it's a

gut-level kind of writing, and on-the-edge kind of writing. Horror is

also really neat because it's always redefining itself. So I'm

extremely pleased to be a horror writer, and would be willing to shout

it from the rooftops that I love horror and that I love what I do.

Wiater: That may work for you, but others have declared that

they don't wish to be so labeled—that it limits their careers to be

thought of as horror writers, even though they don't deny it's an area

of fiction in which they excel.

McCammon: The problem is not in the writing, or in the writers.

The problem is with the publishers. They see horror as primarily a book

with some scary elements, and they market it from that narrow

perspective. But there's so many different kinds of horror, and so many

things going on in horror fiction, that it's very hard to define. But

the publishers will try to define it in terms of the marketplace, and

will push whatever works. I think it's the writer's responsibility to

push the boundaries of what a publisher may feel is "horror

fiction." It's the writer who should really get in there and try

to do different things within the genre, and push those boundaries. And

in that way, he'll eventually reeducate the publishers—and the

audience—as to what horror fiction is.

I'm not sure myself what horror is. But I know it's not just one

thing; it's not just Friday the 13th or The Shining and

it's not just Weaveworld. It's all those elements—and more.

Wiater: Critics say that the genre will never be taken seriously

because it doesn't deal with real events or real people. You should be

writing on a "serious" topic.

McCammon: [angrily] Yeah, that really ticks me off.

Because to me, hell, horror is real. I don't think I or my

colleagues could write it if we didn't think it was a serious subject. I

take that as a great insult when somebody says, "When are you going

to write something serious?" But this is real—it's about life and

death! You know, people who ask that question have never read

horror—they don't know a damn thing about it! And they probably don't

know much about...anything.

Because horror writing has always seemed to me a very liberal,

forward-thinking kind of literature that is not afraid to shake things

up. It's not afraid to be nasty. It's not afraid. It's just not afraid.

And isn't that what art is all about? Horror fiction can be—is—art.

Now art may not necessarily be pleasant or nice to look at. And yet, to

me, the beauty of horror is that there's so many ways to go, there's so

many areas still left undiscovered and unexplored.

Wiater: Are there any taboo areas that you won't touch in your

work for risk of being too offensive? In other words, can there be a

concept as "bad taste" in horror fiction?

McCammon: I don't believe there can be such a thing as bad taste.

There can only be bad writing. You can have the most outrageous scene

with the most extreme violence and handle it in such a way that it'll be

extremely excruciating—but there'll be no blood. So I don't think

there can be any bad taste in creating a scene, only bad writing in

handling it.

Wiater: A major theme in your work is that, no matter how awful

the situation may be, your characters always retain the hope that they

will somehow reach the end of the darkness or the chaos. But don't you

feel the most effective horror lies in dealing with situations which

eventually fade to utter black?

McCammon: But how do you mean "effective"? I tell

stories which are effective to me in terms of hope. But then someone

else might want to tell a story in terms of hopelessness. But my key

word is hope; I think there's hope in any situation. And that's

what motivates my characters to do what they do, because they think,

"There's a way out of this mess...." or, "There's a way I

can transform myself personally..." Again, one voice may want to

deal with horror from this perspective, while another may want to focus

on the darkness. I have different tones in my stories, and hope is not

always the right tone, but the element of hope is in most of my work.

Wiater: You've been described as a writer whose strength lies in

bringing life to his characters rather than just finding the ways of

gruesomely destroying them. Do you feel others are attempting to create

more than just "books with scary elements"?

McCammon: You know, I think horror writers are now like that

Bohemian society in Paris in 1920s, where everybody had their own style

of art, and their own philosophy about art. This one was experimenting

in cubism, and this one in naturalism.... But what they were really all

talking about was the same thing—they were really talking about art.

So it doesn't matter whether we talk today about quiet horror or

splatterpunk because there's a great horror within all these voices. And

I know I'm trying to sound diplomatic, but I'm not: I enjoy all these

spectrums, and there's room for all of them. So to say, "Well,

there should only be quiet horror, no blood and guts," or that it

should be the other way around, diminishes the field. Diminishes the

force of horror itself. It may be that horror is forever undefinable. It

will always have these different voices and moods, and there may be no

way to tame or define it. And that may be one of the great powers

of horror fiction.

Wiater: Do you believe that perhaps the academics have given the

field a legitimacy it didn't have even a decade ago? For example,

science fiction and mystery are genres that have at last been recognized

as worthy of legitimate literary acclaim.

McCammon: Well, I have to admit that my aged relatives don't read

my books because they would find it very uneasy to be around me

[laughs]! But I really do feel there's a change in the wind. I

don't want to say that horror's become respectable—the great thing

about horror is that most of it will never become

respectable—but people are finally listening to what this kind of

fiction can say about the human condition. And it's not only that people

are being scared by the superficial elements of horror fiction. They

really are beginning to realize that there is more to it than just the

scare scenes.

Wiater: You've told me before how horror is in fact the oldest

form of literature, both written and oral.

McCammon: Horror fiction has as its basis the human condition,

and it can talk about that condition in a way that other types of

fiction cannot. It's the idea that this literature that we do has

worth—it's too fun, it's a hell of a lot of fun!—but it has

worth. And I think it has enduring worth. People are beginning to

realize that as well and they're reading horror now as serious

literature. I really believe that. (And I can hear the howls from that

statement all the way across the Atlantic. But I really think it's so.)

The longest running tradition in literature is the horror tale, and it

goes back to Beowulf, and I'm sure it goes back to the oral tales

of "You better not go by the swamp, because there's something in

there...." These tales of warning, of danger—either in a physical

or a mental way—which show the ways others have dealt with it, have

been around a long, long, time. And will be around until the end of

time.

Wiater: A personal favorite of mine among your early novels is

They Thirst. Can you recall how that story originated?

McCammon: Well, I always wanted to do a vampire novel. So I

thought, where would be a good place to set a vampire novel? First it

was going to be set in Chicago, and be about teenage gangs who were

vampires. I did two hundred pages of that book...and you get to a

certain point where it either takes off or it doesn't take off. Well,

that was one that didn't take off [laughs]. I wanted an epic

novel that I could take in a lot of different directions, so the first

thing I did was have a detective who was originally from Hungary, who

had a lot of prior experience with these vampire forces. So, where? Los

Angeles—a lot of different kinds of people out there, different

nationalities. I mean, who says a vampire can't be Jewish, or whatever?

So I went from there, and this time it worked out.

[...]

Wiater: It may at last seem like an appropriate stereotype, but

is it true you write at night and sleep during the day?

McCammon: I start work at about ten at night, and finish up at

about four in the morning. When I'm finishing up a book, as I am now,

I'll get up at about eleven o'clock in the morning and get right back to

work. It takes me about nine months to write a book. I pace myself

pretty well, in terms of doing only about five or six pages a day—and

those are finished pages. When I'm completing a book, I'll double up on

my shift, working seven days a week. I take my summers off. I do write

short stories, but generally I just enjoy the summer.

I enjoy working at night—I just do better at night. I've noticed that

the quality of my work changes somewhat: When I work at night, there's

more of the fantastic and a horrific feeling to it. And in the daylight,

that's when I go back and shape up what I've written the night before.

Wiater: Speaking of stereotypes—and since you founded the

Horror Writers of America—why are people in this business often just

the opposite of what the public expects them to be?

McCammon: Usually when I talk about fellow horror writers, I find

that others ask me, "Aren't those people all weird???" It's

amazing that most of the people in this field are so nice. Really! And I

think it's because we're able to get all this acid out on paper. To get

these bad feelings and impulses out on paper, which so-called normal

people can't do. Everybody has violent impulses sometimes where they'd

just like to rip somebody to pieces; where they're inflicted by some

kind of momentary madness. But we can get it all out on paper! And

we're probably a lot more healthy, mentally, then a lot of these folks

running around. I really believe that.

Wiater: Of course, not everyone is a fan of your work—or the

genre in general. What do you say to those who charge that horror—in

any medium in the mass media—is inherently bad for children, and is

basically of no value whatsoever?

McCammon: Well, life is bad for children, too. Life makes them

grow up, and that can be bad. Like it or not, there are many aspects of

horror fiction which offer clear and very penetrating insights into the

human condition. Yet I can see some very prim and proper person saying

that "Horror fiction is no good, and it should be banned." And

that's been said to me before. After I gave a speech, I once had a

person stand up who was very upset and ask me, Why was I forcing people

to read this stuff? And I said I wasn't forcing anyone to read it.

Because there is nothing wrong with reading horror fiction!

One of the reasons I like it is because there is an element of hope in

most horror fiction; it doesn't all have to be dark. It can be a

glorious human transformation as well as an unfortunate fall from grace.

And a climb to grace. And that's what I believe the best in horror

fiction entails. I think that's fantastic—I think that's fabulous! Of

course, nothing I could say would probably keep anybody from censoring

horror. But it'll never be censored in this house.

Wiater: But what about the critics who charge that, with all the

real-life horrors around us, why dwell upon the subject even more.

McCammon: Horror writers are approaching "real"

horror, but we're doing it in such a way that is, hopefully, artistic

and civilized. And in an educated and thoughtful way. We're not

glorifying madness or murder or child abuse or any other of our

twentieth-century horrors. We're simply trying to make sense out of the

chaos, and in the process, exploring ourselves as well. We have to go

all the way in, to conduct exploratory surgery. And some surgery is done

with a laser, and some with a saw. We may not like what we find, but we

still have to know what's there. For me, that has always been one of the

valid reasons to write horror fiction.

Wiater: So again, you have no misgivings about being recognized

and ultimately packaged as a writer in this genre?

McCammon: Absolutely none. Although some publishers may treat it

as a second-rate literature, it is a first-rate literature, as far as

I'm concerned. I don't believe there's any other kind of literature

that has as much to say, or is as strong. Or as important. I think many

more people should be exposed to the genre. Because when you

consider the term "horror fiction," the average person says,

"Well, it must be...horrible. Or, "Why should I want to read

something that gives me nightmares?" But good horror fiction can

be a wonderful way of stirring things up—of making you appreciate life

all the more because there is so much death and suffering in this world.

Stanley Wiater is an award-winning author, consultant, screenwriter,

and creator and host of the Dark Dreamers television series.

For more information, please visit www.StanleyWiater.com or

www.DarkDreamers.com.

Excerpt copyright © 1990 by Stanley Wiater. All rights reserved. Reprinted

with permission.

|